More and more brands across the world are taking responsibility not only for the production of their clothing but the entire lifespan of the garments they produce, including how clothing is worn, washed, and disposed of; many shunning the idea that disposal is even a viable option.

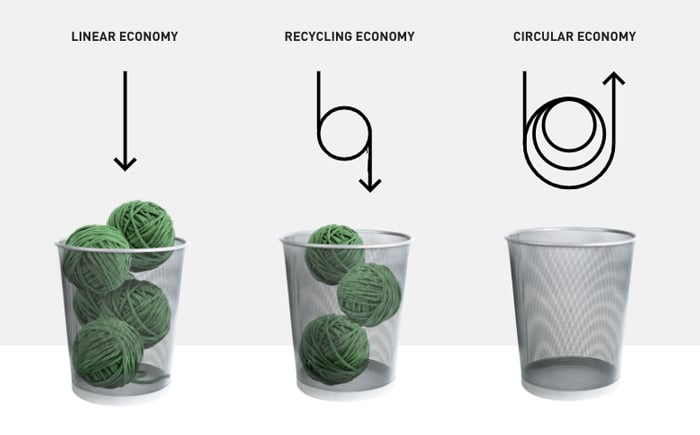

If there was anything that could be branded as “so last season”, it’s the linear approach to, well, anything. But particularly fashion. Increasingly, designers, retailers and consumers are waking to realise that everything they do, wear, buy and even eat should be beneficial for both human and ecological health. For designers particularly, the idea that waste is a design flaw is starting to resonate, with practices such as zero waste, mono-materiality and design for disassembly key to closing the loop.

Perhaps this need to close the loop was brought to public attention in the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s report A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning fashion’s future, which presents an ambitious vision of a new system, based on circular economy principles, that offers benefits to the economy, society and the environment. And, as MacArthur rightly says, we need the whole industry to rally behind it. But while the Ellen MacArthur Foundation champions the need to rid the linear approach, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard took it even further a decade earlier in his iconic book Let my people go surfing, famously saying back in 2006 that “most of the damage we cause to the planet is the result of our own ignorance”.

Linear vs Recycling vs Circular Economy

Amidst the glitz and glamour of the fashion industry is a dark and dirty underbelly; an industry that can cause more harm than good if not managed correctly. Fast fashion is on the rise, as are the world’s sea temperatures. Clothes are being worn less, yet according to the Euromonitor International Apparel & Footwear 2016 Edition, in the past 15 years clothing production has approximately doubled, driven by a growing middle-class population across the globe and increased per capita sales in mature economies. However, it’s not all doom and gloom. The 2017 WRAP report found the amount of clothing in household residual waste destined for landfill has reduced by 14% since 2012, although this amount still adds up to 300,000 tonnes. The same report found that by extending the active life of 50% of UK clothing by just nine months would save 8% carbon, 10% water and 4% waste per tonne of clothing. In addition, if 5% to 10% of clothing sales were via hire and repair models to extend their active life, the savings could be 30 to 60 million cubic metres of water and 80,000 to 160,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Not only does extending a garment’s first - and even second - use phase offer a less impactful environmental solution, renew and repair services can provide growth opportunities for businesses.

Care and repair

A Mend to Extend program is offered by many brands, including Revel Knitwear, which creates luxury hand-knitted pieces for the modern minimalist. If a sweater gets snagged, Revel Knitwear will send its customer a sample of wool to sew into the sweater - should you have the skillset - or it can be posted back for an in-house repair.

“I started the Mend to Extend program to promote people investing in clothing and cherishing their purchases,” says Revel founder Shannyn Lorkin. “I want our customers to be able to easily extend the life of their knit, to hold onto it and enjoy wearing it for as long as possible. It’s important that as a business we are innovative on not only how to create quality, sustainable pieces but also how the customer can continue the life cycle of the garment. By educating on how to wash, care and repair the garment, we are empowering them too.

“I work with wool because it naturally is a first choice with knitting. It can be so strong and last such a long time when cared for well and in that way holds very strong quality. You also don’t need to wash wool very often, you can air it outside when needed, and so therefore is actually low maintenance. I want to reduce our impacts on the environment by making quality clothes that last and have fibres that will break down well.”

Tread a little lighter

Many consumers may not think about fibres when purchasing new clothes. What goes into a garment is just as important as how it was made. Wool, for example, is resistant to stains, odour and wrinkles, with garments made from the fibre requiring less washing and drying, saving time and ultimately reducing the household energy bill. It’s factors such as these which drive conscious consumption. As Dame Vivienne Westwood famously champions: “buy well, choose less, make it last”. Or, “can I wear this item at least 30 times?” as Eco-Age’s Livia Firth has popularised in the 30-Wear Challenge.

“If consumers want to consume fashion more sustainably, the first thing is to buy less, and buy better,” agrees sustainable fashion critic Alden Wicker. “Avoid spending on items that will be dated in a year or two. If you really want to try out a trend, rent it from a place like Rent the Runway. If you want to buy something new, invest in versatile items that are made with high-quality materials that you can wear at least 30 times. Look for items made with 100% Merino wool and other natural fibres.”

“Brands can encourage a more sustainable life for clothing by taking responsibility for the whole life of the clothing they make, from production, to purchase, to the secondhand market, and recycling.”

'Brands and designers must also become problem solvers, creating products with low environmental impacts. “Brands can encourage a more sustainable life for clothing by taking responsibility for the whole life of the clothing they make, from production, to purchase, to the secondhand market, and recycling,” says Wicker. “The goal is to keep it from ever going into the landfill, and instead keep the product and material continuously cycling through the fashion ecosystem. Brands can start by designing clothing with long-term value in mind - it should still be wearable beyond one or two seasons, both because it’s a classic style and because it’s still in good physical shape.”

One such example comes from Swedish sports brand Houdini Sporstwear, which recently announced that 100 per cent of its fabrics are recycled, recyclable, renewable, biodegradable or Bluesign certified.

“Designing for circularity is essential if you look at the systemic perspective of people and planet,” explains the brand’s CEO Eva Karlsson. “Humanity needs to use the planet’s natural resources more wisely and with circular design we can make sure the resources we use don’t get wasted but instead can be used as resources again and again.

“Moving from a linear to circular model will enable us to eliminate the concept of waste, one of humanity’s greatest design flaws of all times. We believe that as a business we have an obligation to strive towards becoming regenerative - a company that contributes to the world rather than take from it.”

Lives long lived

Wool provides the global apparel industry with the most reused and recyclable fibre, of the common apparel fibre types, with data in the UK suggesting a high donation share for wool, three-times more than the fibre's share of new material use. In fact, wool’s recycling industry is 200 years old, so it comes as no surprise wool has the highest share of fibres recycled.

![]()

Most Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies for clothing incorrectly assume that garments are immediately landfilled (or disposed of) at the end of their first life phase. LCA is a young science which is still evolving and environmental ratings agencies such as the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) do not yet account for all life stages in their environmental rating index, known as the HIGG Material Sustainability Index (MSI). The Higg MSI clothes ratings system fails to include a full life cycle of products. Without including key environmental impact stages such as the use phase and garment end-of- life in the MSI, comparisons between fibre types are not meaningful. If not addressed, these inconsistencies could guide well-intentioned consumers towards less sustainable fibre choices.

100% natural, renewable and biodegradable, readily recycled and requiring less laundering, wool has a compelling story to tell at every stage of a garment’s life cycle, with many brands championing the eco-credentials of the fibre. Yet when it comes to consumer education, there is still a long way to go. According to Wicker, not including the use phase or second-life phase in LCA ratings has led to confusion amongst consumers.

“For a simple example, life cycle assessments that compare cotton and plastic bags say that plastic bags are actually anywhere from 100 to 10,000 times better for the environment, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, etc,” said Wicker. “But, that doesn't account for the fact that marine animals eat and choke on plastic bags, and they never biodegrade. Consumers are being asked to compare apples to oranges and make a wild guess as to what is better. So LCAs should absolutely take into account how often the average consumer washes or dry-cleans a material, how many times a material can be worn or used before it starts to fall apart, whether it can (and actually will) be recycled, and how long it takes to biodegrade in the environment. Polyester is technically recyclable, for example, but very little of it is because it has to be a pure, high-quality polyester that is collected and sent back to the one Japanese manufacturer that does that. Right now, with technology being what it is, pure wool and cotton are the most likely to be turned into other products.”